When we talk about soil constraints on revegetation, pH often gets blamed first. Too acidic? Add lime. Too alkaline? Try to correct it.

But as soil scientist Paul Storer explains in this video, pH is only part of the picture — and in biological revegetation programs, it’s often not the limiting factor people think it is. The real action doesn’t happen in the bulk soil. It happens in the rhizosphere — the living zone around roots where microbes can completely reshape conditions for plant success.

What soil pH actually tells us

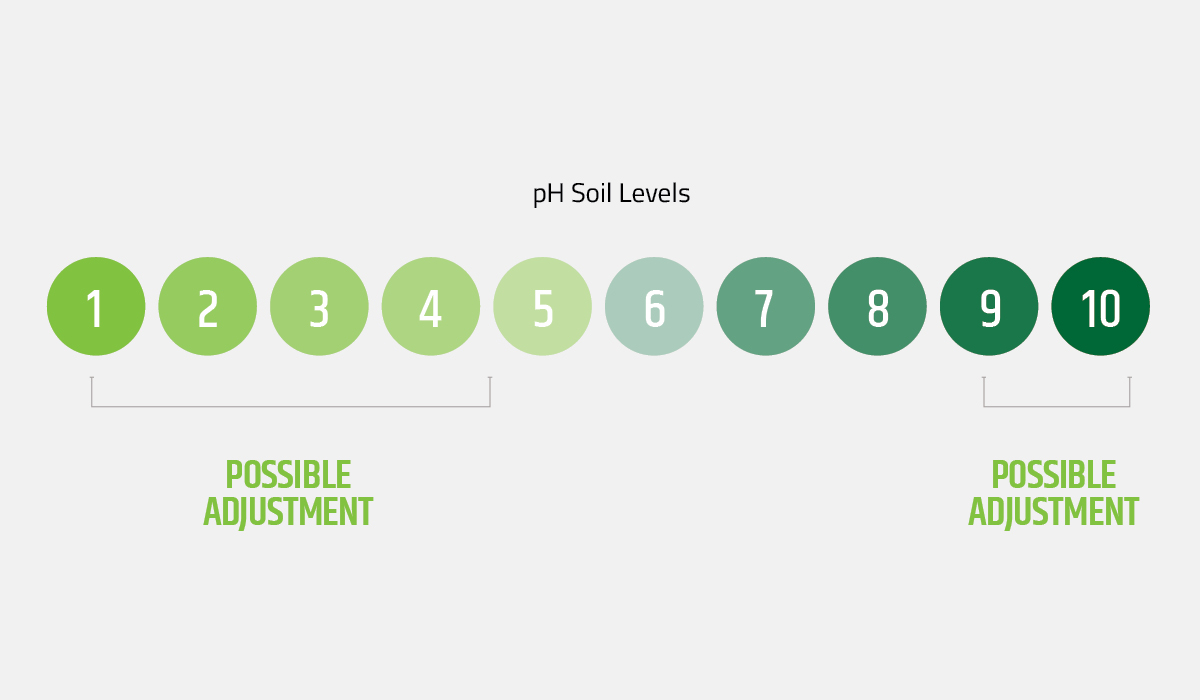

Soil pH is simply a chemical measure of how acidic or alkaline the soil is. And at the extremes, it can seriously restrict plant growth.

In low pH soils (around pH 4–4.5), elements like aluminium and iron can dominate the chemistry. Many plants struggle in these conditions because high aluminium availability can become toxic and restrict growth.

At the other end, high pH soils (pH 8–10) create a different problem – key nutrients such as zinc and manganese can become locked up, meaning plants can’t access them. Zinc is especially important for root development, so if it’s unavailable, plants often establish poorly and fail to thrive long-term.

Traditionally, the solution is simple: force the soil into an “optimal” pH range. That usually means applying large volumes of lime or dolomite to shift acidic soils up toward a target like pH 6.5 – regardless of whether that pH is truly what the plant (or its biology) actually needs.

Why biological systems don’t obsess over bulk pH

In a microbial revegetation program, pH matters – but not in the same way. That’s because microbes don’t just live in the rhizosphere… they engineer it.

When a seed germinates and roots begin to develop, beneficial microbes form around the root system and can create the environmental conditions the plant needs, including adjusting pH locally.

So even if the surrounding soil is pH 4.5, microbes can shift the pH inside the rhizosphere – often by as much as two pH units. That means the plant may experience something closer to pH 6.2–6.5 in its root zone, even though the broader soil remains strongly acidic.

Instead of changing the entire soil profile with tonnes of amendments, we can create a functional pocket of life where roots can actually operate.

And it’s not just about “raising” pH. Different microbial groups naturally lean different ways:

- Bacteria tend to prefer more alkaline conditions

- Fungi generally prefer more acidic conditions

Together, they help condition the rhizosphere toward what the plant needs to grow.

The missing metric: Eh (redox potential)

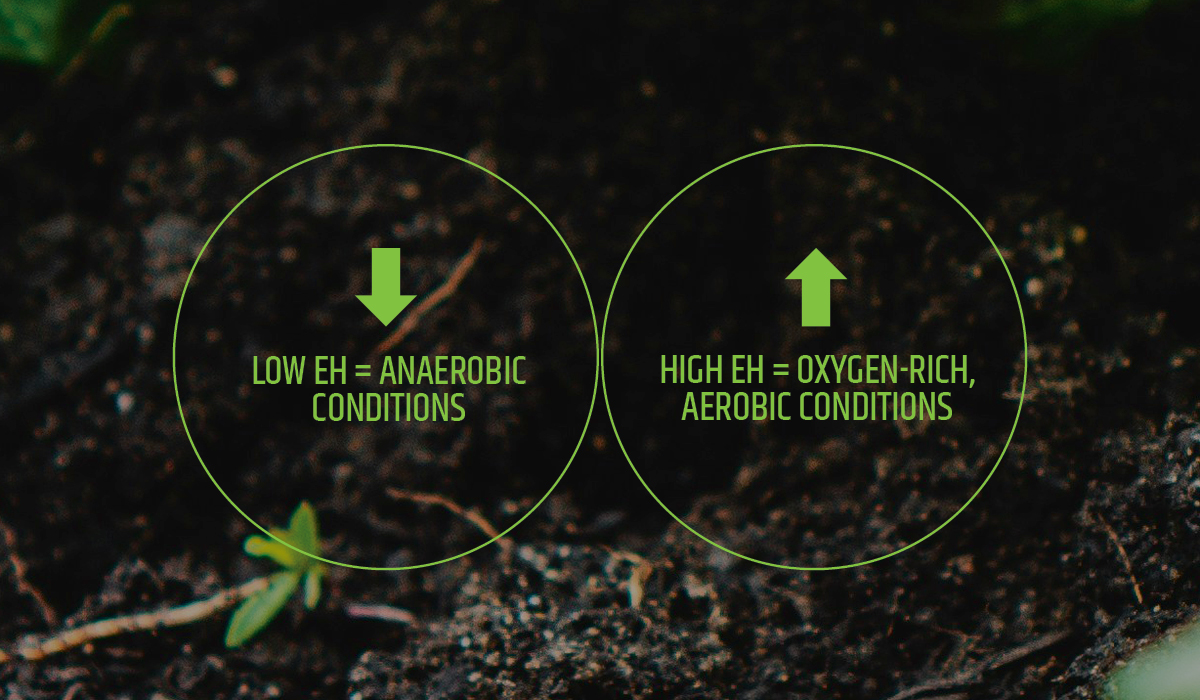

Where conventional programs fixate on pH, microbial programs also pay attention to something many projects ignore entirely: Eh — the redox potential of soil.

If pH is about hydrogen ions, Eh is about electrons, and it’s closely linked to the soil’s energy status. Microbes run on electron transfer – it’s how they generate energy – so Eh tells us whether the soil environment supports the right biology.

In simple terms:

- High Eh = oxygen-rich, aerobic conditions

- Low Eh = anaerobic conditions (often waterlogged, stagnant, biologically hostile for roots)

This matters because root systems don’t like anaerobic zones. And when soils drop into low Eh states, they often become dominated by undesirable microbes, including:

- Denitrifiers (break down nitrogen availability)

- Sulfide-producing bacteria (can release hydrogen sulfide)

- Methanogens (associated with highly anaerobic environments)

On the other hand, soils with healthier Eh conditions support microbes that drive ecosystem function, such as:

- aerobic decomposers

- nitrifiers

- organisms involved in carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycling

And importantly for revegetation: fungi tend to sit in the “middle ground” — they like moderate Eh. That becomes critical because most plants depend heavily on fungi.

Microbial programs rebuild conditions instead of fighting chemistry

In conventional fertiliser systems, nutrient delivery depends heavily on soluble inputs.

But water-soluble nutrition creates major inefficiencies:

- nutrients wash through easily

- phosphorus gets locked up by aluminium or calcium

- roots can only draw nutrients from small “depletion zones”

Phosphorus is especially limited – the transcript notes it may only be accessible from about a millimetre away from the root, meaning even if phosphorus exists in the soil, it may be functionally unreachable.

So the system responds by applying more and more fertiliser.

A biological system moves the opposite way – rather than forcing the bulk soil into compliance, microbes create a buffered rhizosphere that:

- adjusts pH locally

- improves nutrient availability

- expands the functional reach of plant roots (especially via fungi)

- reduces the need for heavy chemical correction

- avoids nutrient excess that can pollute surrounding environments

So when do you adjust pH in a biogrowth program?

The key takeaway is simple – most of the time, you don’t. Only in extreme cases – highly acidic soils (around pH 4.5 or lower) or highly alkaline soils (pH 9–10) – might pH adjustment become necessary.

But even then, it’s approached differently. The goal isn’t to chase a perfect number. It’s to create a workable window where microbes can thrive, form a rhizosphere, and do the buffering themselves. In fact, calcium may still be applied in many projects — but often because the soil is deficient in calcium, not because the goal is to manipulate pH.

Stop chasing perfect pH and build living function

Revegetation success doesn’t come from forcing every hectare of soil into an “ideal” pH range. It comes from rebuilding the biology that can:

- protect roots

- reshape conditions

- unlock nutrients

- and stabilise soil systems long-term

To find out more from Paul Storer about how microbes can create stability, resilience and growth that improves over time, watch the full video.